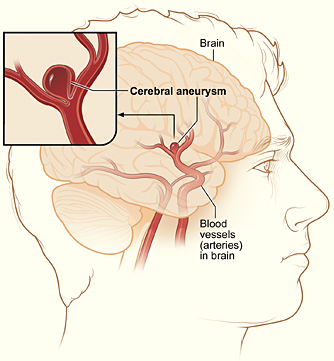

Stroke is a disease often associated with the elderly, but this is not necessarily true. As much as 5% of the population carry a ticking time bomb in their brain, known as a berry aneurysm. An aneurysm is a weakening of the arterial wall, causing a localised ballooning of the vessel. A berry aneurysm is a common type of aneurysm where the ballooning resembles a berry. What is most troubling is that a large proportion of these aneurysms can present very early (usually congenital, meaning you are born with it), with one research suggesting that 1.3% of the population in the age group of 20 to 39 has a berry aneurysm. If this berry aneurysm was to burst, no matter how young and fit you are, you will bleed into the area around your brain (subarachnoid haemorrhage), suddenly develop a severe, crippling headache (“thunderclap headache”), become confused, show signs of stroke such as speech or movement problems, or simply drop dead.

Fortunately, only 10% of people carrying a berry aneurysm suffer a ruptured aneurysm and subsequent brain bleed. The other 90% will carry on living their lives, without ever knowing that they had a time bomb in their brain.

Certain factors make the risk of the aneurysm bursting go up, such as high blood pressure, which can be caused by a stressful lifestyle or smoking. But in some cases, as explained above, even a healthy teenager could suddenly drop to the ground with a massive brain haemorrhage.

Berry aneurysms are only one of many ways death could strike unnoticed, no matter how young you may be. You could live a long and healthy life and die peacefully in your sleep when you are 90 years old, or you may have a stroke and drop dead in a few minutes’ time. For all you know, a bus might run you over tomorrow, with no warning whatsoever. Ergo, youth is not an excuse to waste the day you are given. You do not have to achieve something great, or be productive, but at least spend your day knowing that you are doing everything in your power to make yourself happy, without harming your health, your future or other people.