(Learn more about the organs of the human bodies in other posts in the Viscera series here: https://jineralknowledge.com/tag/viscera/?order=asc)

Everyone knows that we need oxygen to survive. The way we get oxygen from the atmosphere is through our lungs – the organ where gas exchange takes place. The pair of lungs take up a large proportion of the chest cavity and they link up with each other to form the trachea (windpipe). The left lung is slightly smaller to accommodate for the heart.

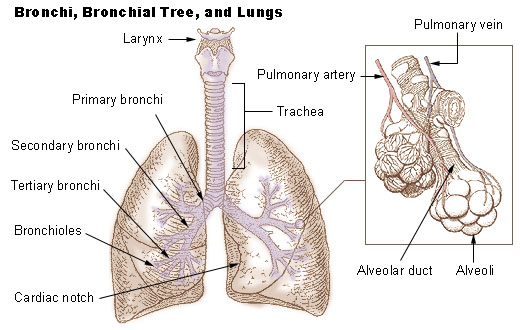

The lung is extremely soft and light, so much that it floats on water. It is essentially made up of an intricate tree-like system of airways, which become narrower and narrower as it divides out from the trachea. Since every airway divides up, the number of airways increases exponentially. Every bronchiole (small airways) ends in a bubble-like sac called an alveolus. Because of the sheer number of alveoli, the lungs actually have a total surface area the size of a tennis court. To picture this, scrunch up a piece of newspaper into a ball to pack a large surface area into a small space. The massive surface area allows for enough gas exchange to occur to give us the oxygen we need and excrete all the carbon dioxide we produce.

When we take a breath in, the chest cavity expands and stretches the lungs in all directions because of the negative pressure (like a vacuum). Air fills the airways all the way to the alveoli. The alveoli are extremely thin; so thin that the oxygen in the air effortlessly seeps through into the blood vessels that surround the alveoli. On the other hand, carbon dioxide seeps out of the blood into the alveoli, which is then breathed out as the muscles of your ribcage contract to force the air out. This process is called gas exchange and is driven by diffusion – the movement of particles from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration (like how dye spreads throughout water).

It is well-known that smoking is bad for your lungs. This is because of two major reasons: COPD and lung cancer. COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder) is when your lungs become so damaged by smoking that they cannot function, leading to hypoxia (lack of oxygen) and hypercapnia (excess of carbon dioxide). Smoking causes inflammation in the lungs, which causes airways to shut down from swelling and mucus, while destroying the fine walls of the alveoli. This causes the alveoli to thicken from scarring and less elastic due to the destruction of elastic tissue. Ultimately, the lungs become hyperinflated as the patient cannot breathe out air properly and the lungs are not elastic enough to return to their original shape and size. Ergo, the patient becomes progressively breathless, gasping for breath as they suffer a sensation of impending death as the carbon dioxide level builds and the oxygen level falls.